Editor's note: This story is part of The Marathons Series, a collection of articles written by faculty and students. It's a space to talk about work in progress and the process of research—think of it as the journey rather than the destination. We hope these stories help you learn something new and get in touch with your geeky side.

I began writing Isle of Rum in 2016, when it seemed as if formal relations between the US and Cuba would be restored. President Obama had given a speech in Havana, and while he didn’t state it explicitly, he seemed to welcome the opportunity to promote private enterprise on the island. As someone who teaches advertising, this seemed like an important moment to study a socialist country’s pivot toward capitalism. I soon realized, however, that this wasn’t necessarily new territory. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1993, Cuba had has partnered with transnational corporations.

Cuban rum seemed to be the most appropriate vehicle in which to explore Cuba’s adventures in capitalism. Not only is rum linked to Cuba itself, but its Havana Club brand was one of Cuba’s first joint ventures. Today, Cuba produces the rum, while Pernod Ricard, a French liquor conglomerate, distributes and markets it. This arrangement has introduced an army of cultural brokers (ad executives, music producers, filmmakers, and so forth) who are tasked with selling Cuban rum to international markets.

So yes, my book is about rum, but it’s really about these cultural brokers, based primarily in the United States and Western Europe, who profit by selling a narrow version of Cuba to western consumers. To understand how these cultural brokers represent Cuba, I did a combination of archival research, fieldwork, and industry analysis.

Rum in all the right places

For much of its early history, rum was considered a product consumed by slaves and poor whites. It wasn’t until distilleries began to recognize the market potential for Cuban rum that they began to invest in advertising and branding, which was designed to elevate the status of rum. To examine how marketers have leveraged the “Cubanness” of rum over time, I analyzed advertisements that ran in 19th and early 20th century publications such as La Ilustración Artística, a Spanish arts publication, as well as Cuban lifestyle magazines such as Carteles and Bohemia.

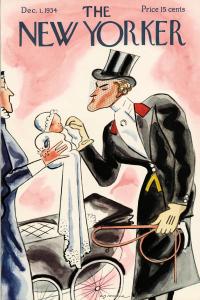

When José Arechabala S.A. launched Havana Club in 1934, the brand was meant primarily for the American consumer. To position itself as a premium product for a cosmopolitan audience, Havana Club placed ads in The New York Times, as well as upscale American magazines like Esquire and The New Yorker. You learn a lot about a society, its culture, and its economy through its advertising.

But Where Has All the Rum Gone?

The story of Cuban rum is a story of global movement, and this is certainly true of Havana Club. The company’s founder, José Arechabala, left the Spanish province of Viscaya at age 14 and sailed to Cárdenas, Cuba, which is where he made his fortune. After the Cuban Revolution of 1959, the business was expropriated by the Cuban government. Like other wealthy families of the time, the Arechabala family resettled in Miami.

I wanted to follow Arechabala’s journey, and so I traveled to Gordexola, Spain, the town where he was born and raised. I also visited Cárdenas and then Miami. The original distillery is still there in Cárdenas, although the production of Havana Club has moved to a new distillery meant to accommodate large-scale, global production.

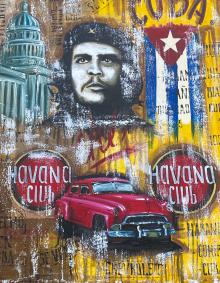

I also wanted to get a sense of global nature of rum production and so I traveled to Puerto Rico, where longtime competitor Bacardí established its production facilities after exile from Cuba. I also conducted field research in Havana and Trinidad, to understand the brand’s importance to the Cuba’s tourism industry. Today, Havana Club exists alongside Che Guevara and 1950s-era automobiles as the main signifiers of Cuba.

Truth in Advertising

Selling Cuba can be tricky business. For many Americans, Cuba signifies repression and poverty. Yet for would-be tourists, Cuba is the embodiment of rich cultural expression. And for many across the Spanish-speaking world, Cuba remains a symbol of resistance to US hegemony. The challenge for advertisers, therefore, is to cultivate a version of Cuban authenticity that is most conducive to selling rum to international markets.

To understand the strategies used by the marketers associated with Havana Club, I looked at two sets of industry discourses. First, there are the strategy documents, in which M&C Saatchi, Havana Club’s advertising agency, explicitly reveal their strategies for leveraging Cuban culture to sell rum. The second are the cultural products themselves. These include the advertising campaigns, the albums, films, and curated art exhibitions that have been produced under the Havana Club brand name.

What does advertising look like when it’s produced on behalf of a socialist country? At first, the campaigns reflected a distinct sensibility, a sort of celebration of the socialist system. The ad below, for example, blurs the line between high culture and popular culture and there is no product shot. Over time, however, their campaigns have become more commercial in nature, likely due to increasing pressures to sell the product.

Like other commodities, Cuban rum has a complicated and dark history. It also reflects an ongoing tradition of foreign exploitation and involves a whole army of professionals who broker in symbolic meaning. Advertising often obscures these realities. These truths are worth remembering the next time you order that Daquirí or Mojito.